Cold New Light

Some recommendations for New Year's Day

The best hangover cure I’ve ever heard of is one I’ve never been in a position to take. It comes from my father. If memory serves (I texted him asking only for permission to share, not a restatement of the procedure), it consists of, first, arriving at work around 5 a.m., that is, on time, a crucial step in alleviating what Kingsley Amis, the greatest writer of the gueule de bois, called the ‘metaphysical’ hangover, which he defined as, “that ineffable compound of depression, sadness (these two are not the same), anxiety, self-hatred, sense of failure and fear for the future.”1 Second, have that work be marine construction, specifically on a barge that travels slowly up and down the salt rivers of Cape Cod. Once the barge is underway, you should tie a long line around your waist, secure the other end to a stern cleat, and, having leapt into the cool water, allow yourself to be towed, floating in the gently churning foam of the vessel’s wake, all the way to the job site. In his telling, you emerge feeling as fresh as if you’d gone to bed at a sensible hour with a glass of warm milk.

Obviously, there are some preconditions here that most of us cannot meet. Except for the very strongest and vainest among us, this is a cure that can only be taken in summertime. It will also require you trusting your knot-tying skills even in your diminished state, as well as some particularly tolerant coworkers. And, of course, you’ll have to have a job that, I’d imagine, not terribly many people are willing or able to get.

But there is a lot to learn here, both for the morning after and for life. It requires getting up and doing what you planned on doing. (Lest I sound too much like a rise-and-grinder, I want to emphasize that this is not a moral accomplishment—Descartes invented his coordinates system by laying in bed until noon and watching a fly on his ceiling—but a practical necessity. Most of us assume that if we feel bad, we’ll feel better if we stay in bed or, at the most, remove ourselves directly to the couch. In instances of real illness, this is probably true, but in cases of self-made or self-perpetuating diminishment, be it a hangover or persistent anxiety, getting up and out will do you much better than hanging around. It’s an awful fact of life, but it’s true.)

It also requires paying attention to how you feel and how you want to feel, not what you’ve done to get that way. Dwelling on the latter is the nastiest part of any hangover, and a cure like this one compels a mindset that you can adopt in any unpropitious circumstances, namely: when you feel terrible, accept that you feel terrible and do what you can to fix it. The time for adjudicating the wisdom the choices you made to make you feel that way, if it ever comes, is not now. Again, I’m not advocating for any kind of moralism here—or amoralism, which is simply moralism when scared of its own shadow—but a principled adherence to the rule over and against the turbulence of the exception. Incidentally, if the brief academic fad of experimental philosophy were of any value at all (it’s not), it might be worth including hangover remedies in a study of Aristotle’s ethics.

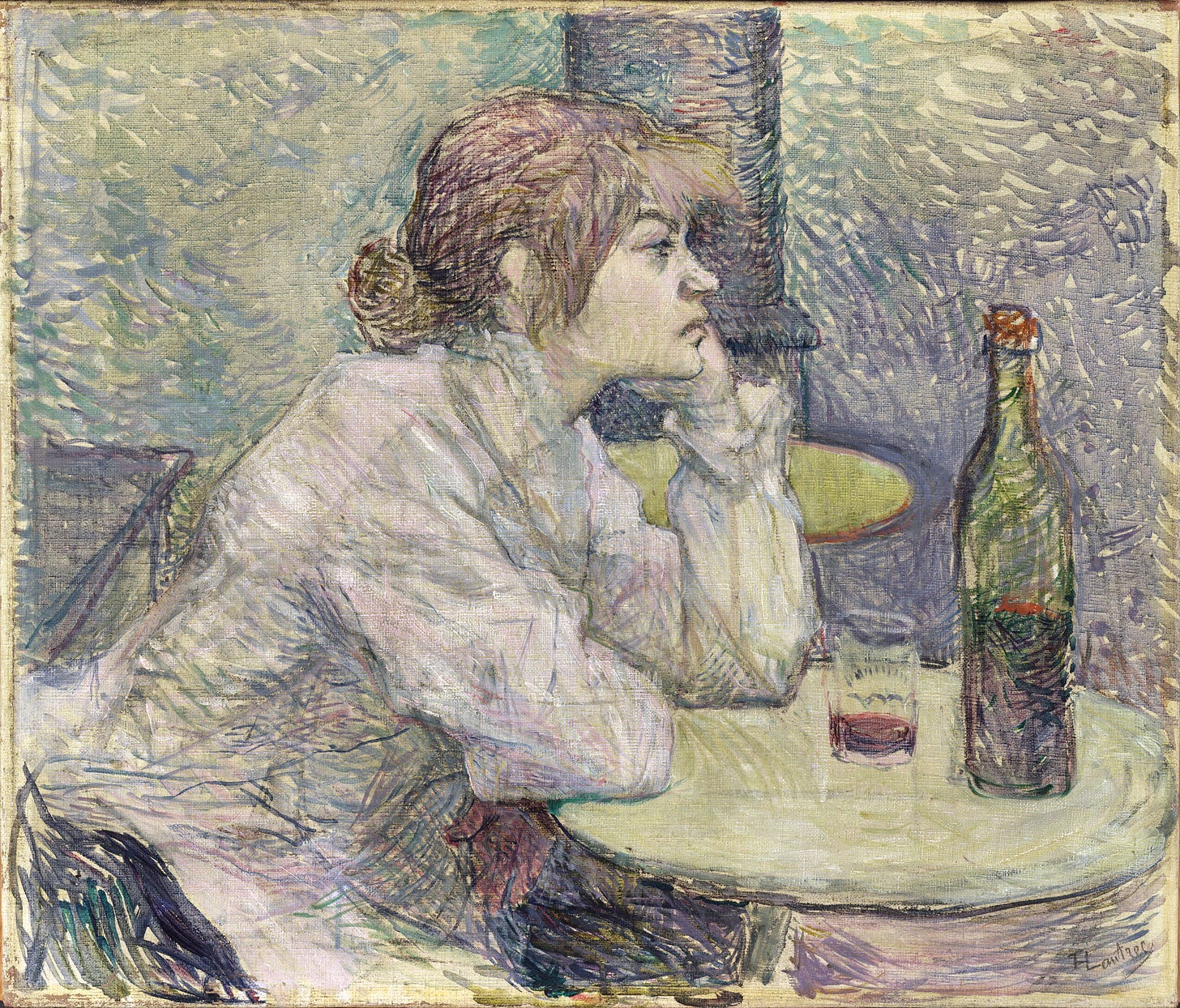

It would also lend some support some to the Philosopher’s poetics, particularly the cathartic effective of tragedy. Chances are, if you’re currently in rough shape, you won’t be at work, but at home, wondering what to do. Amis heartily recommends reading and music, and even, “going off and gazing at some painting, building or bit of statuary,” with the intention of a bit of ritualized emotional processing. “The structure,” he writes,” of…hangover reading and hangover listening, rests on the principle that you must feel worse emotionally before you start to feel better. A good cry is the initial aim.” I would add that it’s best not to go for anything that depicts something you might have directly experienced yourself, especially recently—break ups, death of a parent, career failures, etc.—as this may send you down precisely the spiral you’re hoping to avoid. Choose instead the big picture, existential, unavoidable stuff, which gives you the best of both worlds: the comfort of distance and the perspective of relative scale.

A few recommendations:

Listen:

Schubert’s posthumous quintet, particularly the opening slow movement, which he wrote as knew he was dying and is almost unendurably beautiful. The pianist Artur Rubenstein described it as the composer’s “entrance to Heaven…the feeling of the nothing, of entering death, resigned and happy.” Follow this up with Schubert’s “Trout” quintet, which is my favorite piece of music and is the closest equivalent to floating in cool, running water of which I am aware.

Eric Dolphy’s “Something Sweet, Something Tender.” Tread carefully here, since it might also drive you insane, but some of us find its austere, uncompromising integrity a nice foil to the rottenness we believe we’ve discovered at the core of our own being. If you can hear what I’m trying to tell you, the song seems to say, maybe it’s not so bad after all.

John Zorn’s Virtue. A gorgeous acoustic guitar trio featuring arguably the three most compelling players alive (Julian Lage, Bill Frisell, and Gyan Riley) inspired by the life of Julian of Norwich. By turns abstract and delightfully listenable, this is a wonderful album to carry you through. As Julian herself said, “All shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of things shall be well.”

Watch:

The Seventh Seal. Its beauty and wisdom have been staled by repetition—and it is a bit silly, to be fair—but if you’re really hurting, the knight’s valiant embrace of his fate is the perfect mirror to your own bravery in getting through the day.

Phantom Thread. One of the great explorations of the proposition that care and love are there for you, waiting to be found, no matter what a shit you are.

Into Great Silence. An intimate portrait of the daily life of the Carthusian monks living at Grand Chartreuse. The director sent the monks a letter in 1984, asking to film them, to which they responded that they needed to think about it. Sixteen years later, they granted him permission. The resulting film is a cascade of purifying light.

Read:

The Iliad, particularly Book 24, when Priam comes in disguise to beg Achilles for his son’s body. What better spiritual preparation for your own mid-afternoon Chinese delivery than when the two bitter enemies, bound together in mutual hatred not only by circumstance but by their deeds, find accord over the endlessness of human suffering, decide it is time to eat, whatever their grief. “And Niobe, gaunt, worn to the bone with weeping, turned her thoughts to food.” Couldn’t have said it better myself, to be quite honest.

Moby Dick, especially chapter 42, the “Whiteness of the Whale.” You might have spent the morning feeling haunted, hunted even, by an unnamed dread and terror of what lay beneath the surface of the world. This masterpiece of the American sublime (which is also the American berserk) may convince you that you were, in fact, correct to believe so, which, given the miraculous paradox of art, will be a comfort.

P.G. Wodehouse, Carry on, Jeeves. Close out the proceedings with the story of how Bertie came to employ Jeeves. You’ve earned it. You might even watch the amazing Fry and Laurie adaptation. If you can stomach the hair of the dog therein described, I salute you.

Good luck.

Amis is, unsurprisingly, the author of what is perhaps the best description of a hangover in English literature. It is also, at this point, among his best-remembered writing. In case you haven’t seen it before, here it is, from Lucky Jim: “Dixon was alive again. Consciousness was upon him before he could get out of the way; not for him the slow, gracious wandering from the halls of sleep, but a summary, forcible ejection. He lay sprawled, too wicked to move, spewed up like a broken spider-crab on the tarry shingle of the morning. The light did him harm, but not as much as looking at things did; he resolved, having done it once, never to move his eyeballs again. A dusty thudding in his head made the scene before him beat like a pulse. His mouth had been used as a latrine by some small creature of the night, and then as its mausoleum. During the night, too, he’d somehow been on a cross-country run and then been expertly beaten up by secret police. He felt bad.”

Thank you. I am so much more fortunate than most, but 2025 was, in the end, too much for me. I have been struggling to get through my normal routine for about two months and recently decided (was forced to?) to just pare my obligations and interactions down to the bare minimum of decency and attend primarily to recovering my balance. I’m sure I’m not alone in this, nor in being grateful for permission to step back and heal.

Schubert and Jeeves are excellent suggestions.

Enjoyed your piece. Thank you from Cape Cod where we double our knots just in case.